Plant sexuality

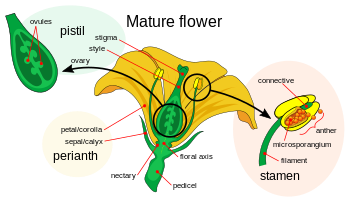

Diagram showing the sexual parts of a mature flower

It was

Rudolf Camerarius

(1665–1721) who was the first to establish plant sexuality conclusively

by experiment. He declared in a letter to a colleague dated 1694 and

titled

De Sexu Plantarum Epistola

that “no ovules of plants could ever develop into seeds from the female

style and ovary without first being prepared by the pollen from the

stamens, the male sexual organs of the plant".

Much was learned about plant sexuality by unravelling the reproductive mechanisms of mosses, liverworts and algae. In his

Vergleichende Untersuchungen of 1851

Wilhelm Hofmeister

(1824–1877) starting with the ferns and bryophytes demonstrated that

the process of sexual reproduction in plants entails an “alternation of

generations” between

sporophytes and

gametophytes.

This initiated the new field of

comparative morphology which, largely through the combined work of

William Farlow (1844–1919),

Nathanael Pringsheim (1823–1894),

Frederick Bower,

Eduard Strasburger and others, established that an "alternation of generations" occurs throughout the plant kingdom.

Some time later the German academic and natural historian

Joseph Kölreuter

(1733–1806) extended this work by noting the function of nectar in

attracting pollinators and the role of wind and insects in pollination.

He also produced deliberate hybrids, observed the microscopic structure

of pollen grains and how the transfer of matter from the pollen to the

ovary inducing the formation of the embryo.

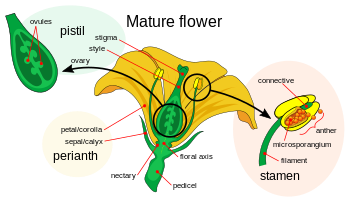

Angiosperm (flowering plant) life cycle showing alternation of generations

One hundred years after Camerarius, in 1793,

Christian Sprengel

(1750–1816) broadened the understanding of flowers by describing the

role of nectar guides in pollination, the adaptive floral mechanisms

used for pollination, and the prevalence of cross-pollination, even

though male and female parts are usually together on the same flower.

Nineteenth century foundations of modern botany

In about the mid-19th century scientific communication changed. Until

this time ideas were largely exchanged by reading the works of

authoritative individuals who dominated in their field: these were often

wealthy and influential "gentlemen scientists". Now research was

reported by the publication of “papers” that emanated from research

“schools” that promoted the questioning of conventional wisdom. This

process had started in the late 18th century when specialist journals

began to appear.

Even so, botany was greatly stimulated by the appearance of the first “modern” text book,

Matthias Schleiden's (1804–1881)

Grundzüge der Wissenschaftlichen Botanik, published in English in 1849 as

Principles of Scientific Botany.

By 1850 an invigorated organic chemistry had revealed the structure of many plant constituents.

Although the great era of plant classification had now passed the work of description continued.

Augustin de Candolle (1778–1841) succeeded

Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu in managing the botanical project

Prodromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Vegetabilis

(1824–1841) which involved 35 authors: it contained all the

dicotyledons known in his day, some 58000 species in 161 families, and

he doubled the number of recognized plant families, the work being

completed by his son

Alphonse (1806–1893) in the years from 1841 to 1873.

No comments:

Post a Comment